How many other seemingly banal questions are literally constantly before our eyes. However, we never tried to find answers to them because we did not notice this question - we got used to it. But often such questions hide interesting, deep and sometimes simply elegant answers.

Have you ever wondered why Hebrew and Arabic writing have one distinct feature, namely writing from right to left? It turns out there is a very practical explanation for this.

Semitic languages, which include both Arabic and Hebrew, are among the oldest on the planet. They originated at a time when no one could even dream of paper, because it appeared only about two thousand years ago. Hebrew and Arabic writing developed from ancient Babylonian cuneiform writing, and Western writing traditions evolved from ancient Egyptian papyrus writing.

To explain clearly what is the difference between them, let’s use our imagination. Imagine that there is papyrus in front of you, and in your hands you have a stylus (a thin knife). We cut hieroglyphs with our right hand (85% of people are right-handed). At the same time, what is written to the right of us is closed, but what is written to the left is clearly visible. The question arises: how do you prefer to write? Of course, from left to right, since it is so convenient to see what has already been written.

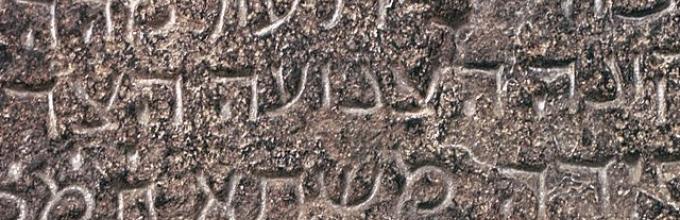

Now take a stone, a hammer and a chisel in your hands. Hammer in the right hand (85%), chisel in the left. Let's start carving cuneiform hieroglyphs. The left hand with the chisel reliably covers us from what is written on the left, but what is written on the right is clearly visible to us. How is it more convenient for us to write? In this case - from right to left.

By the way, if you take a closer look at the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, you will notice that their peculiar configuration indicates that the letters were originally carved on something solid. It is much easier to draw such letters with a chisel rather than with a pen.

Of course, since then the stone has ceased to be the only long-term keeper of information, but the rules of writing have already been formed, so it was decided not to radically change the rules of writing.

Do you agree with this version?

Have you ever wondered why Hebrew and Arabic writing have one distinct feature, namely writing from right to left? It turns out there is a very practical explanation for this.

The fact is that Jewish and Arabic writing arose on the basis of ancient Babylonian cuneiform writing, and the Western tradition of writing - from ancient Egyptian papyrus writing.

To explain clearly what is the difference between them, let’s use our imagination. Imagine that there is papyrus in front of you, and in your hands you have a stylus (a thin knife). We cut hieroglyphs with our right hand (85% of people are right-handed). At the same time, what is written to the right of us is closed, but what is written to the left is clearly visible. The question arises: how do you prefer to write? Of course, from left to right, since it is so convenient to see what has already been written.

Now take a stone, a hammer and a chisel in your hands. Hammer in the right hand (85%), chisel in the left. Let's start carving cuneiform hieroglyphs. The left hand with the chisel reliably covers us from what is written on the left, but what is written on the right is clearly visible to us. How is it more convenient for us to write? In this case, from right to left.

By the way, if you take a closer look at the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, you will notice that their peculiar configuration indicates that the letters were originally carved on something solid. It is much easier to draw such letters with a chisel rather than with a pen.

Of course, since then the stone has ceased to be the only long-term keeper of information, but the rules of writing have already been formed, so it was decided not to radically change the rules of writing.

I remember when I first learned as a child that some peoples, for example, Arabs and Jews, write from right to left, I was very surprised. It seemed incomprehensible to me how one could write like that. After all, this is terribly inconvenient!

I even tried to write something in the opposite direction, but almost immediately I smeared everything with the hand I was holding the pen with.

To my questions about why Jews and Arabs write this way, no one gave an intelligible answer. Therefore, for a long time I had to be content with the explanation that it was just their custom.

However, the answer to this riddle haunted me even as I grew up. It seemed to me that there must be a good reason for writing in the “wrong” direction. And in the end it turned out that this was indeed the case!

It turned out that everything is explained quite simply and logically. The fact is that Semitic languages, which include both Arabic and Hebrew, are among the oldest on the planet. They originated at a time when no one could even dream of paper, because it appeared only about two thousand years ago.

Nevertheless, people needed to somehow record information, so they carved writing on stone. Now let’s imagine how it will be more convenient for right-handed people, who make up 85% of us on earth, to wield a hammer and chisel? Of course, it is more convenient to do this by holding the chisel in your left hand and hitting it with a hammer held in your right. And in this case, it is most convenient to write from right to left!

By the way, take a closer look at the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Their peculiar configuration indicates that the letters were originally carved on something solid. It is much easier to draw such letters with a chisel rather than with a pen.

Although since then the stone has ceased to be the only long-lasting keeper of information, the rules of writing have already been formed, so no one began to radically change them.

This is how the riddle about the direction of writing in Hebrew and Arabic is simply explained. If this was a discovery for you, be sure to share your new knowledge with your friends.

- For each character in the line, the directionality is calculated;

- The line breaks into blocks of the same direction;

- The blocks are arranged in the order specified by the base direction.

The directionality of each symbol is affected by its type and the directionality of neighboring symbols.

Three types of characters

1) Strongly targeted(or strongly typed) - for example, letters. Their direction is predetermined - for most characters it is LTR, for Arabic and Hebrew - RTL.

The words in the picture are entirely strictly typed:

2) Neutral- for example, punctuation marks or spaces. Their direction is not given explicitly, they are directed in the same way as neighboring highly directional symbols.

The comma between the left-to-right “o” and “w” in the “Hello, world” line takes their direction in both basic LTR and RTL:

But what if a neutrally directional symbol falls between two highly directional symbols of different directions? Such a symbol takes on a basic orientation.

This is where the placement of “++” in one case between the unidirectional “C” and “a”, and in the other between the multidirectional “C” and the Arabic “و”, leads to different results:

The same thing happens with neutral characters at the end of a line:

3) Weakly directed(or weakly typed) - for example, numbers. They have their own direction, but do not affect the surrounding symbols in any way.

Continuous words of numbers line up from left to right, but two numbers in a row separated by a neutral character will follow each other from right to left if the basic RTL direction is specified:

An even more obvious case is a number in which the digits are separated by a space:

In this case, it is allowed to separate numbers with a dot, comma, colon - these separators are also weakly directed (for more details, see the specification):

Directional run

Consecutive symbols of the same direction are combined into blocks (directional run). These blocks are lined up one after another in the order determined by the basic direction:

Weakly directed numbers, despite the fact that they have their own directionality, do not affect the formation of blocks, which can lead to the following result - they continue the previous directed block:

Mirror symbols

Some characters have different shapes in different contexts - for example, an opening bracket in RTL will look like a closing bracket in LTR (which is logical, because the content in the brackets will come after - that is, to the left of it).

In most cases, this does not create problems, but if the brackets accidentally turn out to be in different directions, visually they will look in the same direction. For example, if the parenthesis is at the end of the line:

Taking control of order

As we saw above, often the text according to these rules is not formatted the way we would like.

In this case, we come in handy with tools for embedding the desired direction into an existing context or redefining the directions of specific symbols.

Isolation

We have already become acquainted with setting the base direction above: this is done by the dir attribute. This is a global attribute and applies to any element.

dir creates a new embedding level and isolates the content from the external context. The content inside is directed according to the attribute value, and the outer direction of the container itself becomes neutral.

Setting the dir attribute explicitly avoids almost all mixed text formatting problems:

أنا أحب C++ java

If the direction of the content is not known in advance, you can specify auto as the value of the dir attribute. Then the direction of the content will be determined using “some heuristics” - it will simply be taken from the first strictly typed character that comes across.

(comment)

The tag works the same way and the css rule unicode-bidi: isolate:

Landmark: (name)- (distance)

Embedding

You can open a new level of embedding without isolation - the unicode-bidi: embed rule, in combination with the desired value of the direction rule, determines both the direction inside the element and its directionality outside. But in practice this is almost never necessary.

Override

or unicode-bidi: bidi-override; direction: rtl. Overrides the direction of each character within an element. It should be used extremely rarely (for example, if you need to swap two specific characters) and remember to isolate child elements.

Hello, world!

In this case, from the outside the element is interpreted as strongly directional. To make it behave like isolate on the outside but bidi-override on the inside, you need to use unicode-bidi: isolate-override .

Control characters (marks)

Inserting control characters is a nasty technique, but it is useful when we don't have access to the markup but do have access to the content. For example, these could simply be invisible highly directional characters, and ( / or \u200e / \u200f). They help set the desired direction for a neutral symbol.

For example, in this case, for the exclamation mark at the end of a line to take the LTR direction, it must be between two LTR characters:

Hello, world!

Also, any logic described above is implemented through control characters. For isolation - LRI/RLI, for redefinition - LRO/RLO, etc. - see detailed guide on control characters.

Browser support

Unfortunately, in IE the tag , dir="auto" and their corresponding CSS rules are not supported. In addition, the specification of these rules is still at the Editor's Draft stage.

If you need an analogue of dir="auto" that works in any browser, you can parse the content with regular programming and set the dir attribute yourself. But it’s better, of course, not to do that.

HTML or CSS?

Definitely, if possible, you need to control the direction of the text through the HTML dir attribute and the tag rather than through CSS rules. The direction of the text is not stylization, it is part of the content. The page can be inserted through some instant view or read through an RSS-reader.

Before conclusion: a little pain

We got acquainted with the theory. But knowing the theory does not free you from the need to suffer.

The main problem that I encountered in the very first minutes of development for the RTL language was its foreignness. We write code from left to right. My system, browser and editor run from left to right, all of our internal products run from left to right. Therefore, as soon as the Arabic language enters this space, everything is bad and painful:

Text manipulation

If the characters on the screen are not in the same order as they actually appear on the line, what happens if you try to edit bidirectional text? Or at least select and copy part of it?

Nothing good. Try it yourself:

Landmarks: Landmarks - 600 m, Landmarks - 1.2 km

azbycxdwevfugthsirjqkplom n

Code manipulation

And the same thing happens when editing code in the editor and code review - it’s a pain.

You can't even be sure about the order of the elements in an array:

Or worse, the code doesn't look valid at all:

There are many theories about the origin of writing, but it should be understood that none of them can be considered one hundred percent correct - we are talking about processes dating back several thousand years, about which no written (pardon the pun) evidence has survived. The same can be said about other “prehistory of civilization”: we will never know exactly where the first Indo-Europeans lived and what their language sounded like, who the first people who crossed the Bering Strait were, and in what year the dog was first domesticated - we can only make reconstructions and assumptions varying degrees of validity.

However, most scholars now associate the direction of writing with the type of writing implements originally used. There are two main options here.

The text is written with some kind of device reminiscent of a modern pen (stylus, pointed tube, etc.) on a soft surface, and either a coloring matter is distributed over this surface (ink, ink, etc. on paper, papyrus, etc.), or marks on this surface are squeezed out/scratched, but without much effort (wax, birch bark, soft clay, etc.). With this method of writing, it is most convenient to hold the instrument in the right hand (more than 90% of people are right-handed) with the most developed fingers (index, middle and thumb). In this case, writing from left to right turns out to be much more organic, because, firstly, the writer’s hand does not cover what has already been written and you can constantly consult it, and secondly, when using a dye, there is no risk of smearing it with your hand or sleeve.

The text is carved on a hard surface (stone, wood) using a cutting tool (chisel, etc.) and a beater (hammer, etc.). In this case, the hammer is usually held with the right hand (>90% of people are right-handed, and their right hand is stronger), and the chisel is held with the left; Accordingly, it is more convenient to “write” from right to left, since the hammer does not interfere with the view of the sign being knocked out at the moment.

The main method of writing in most human civilizations, for obvious reasons, was the first (soft surface + paint/scratching): it is simple and does not require much physical effort. Therefore, most known writing systems use left-to-right writing. Modern right-to-left writing systems apparently have historical roots in the second version, but these processes are so distant in time that we cannot say for sure that this was the case.

As for other methods of writing, they are derived from those indicated. Eastern writing from top to bottom is the same writing from left to right, which developed due to the fact that writing material was rolled into gradually unfolding rolls. Near Asian boustrophedon (

is also a variant of writing from left to right, in which the surface (tablet) was rotated 180 degrees at the end of each line.